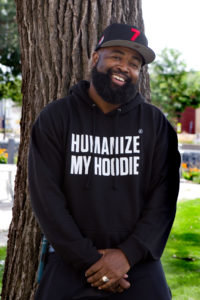

Hamline University adjunct criminal justice professor Jason Sole calls himself a survivor of the War on Drugs. He went from being a soldier on the streets to being a scholar. (Photo by Margie O’Loughlin)[/caption]

Hamline University adjunct criminal justice professor Jason Sole calls himself a survivor of the War on Drugs. He went from being a soldier on the streets to being a scholar. (Photo by Margie O’Loughlin)[/caption]

Jason Sole is feeling peaceful these days. The former drug dealer, street gang member, and three-time convicted felon has succeeded in turning his life around. With criminal justice degrees under his belt, he is focused on creating a radical new definition of criminality – and policing – so there can be justice for all.

In his 42 years, Sole has done some bad things, and taken some hard knocks for them.

Raised on Chicago’s South Side, Sole was born into poverty in 1978. His father was (and still is) a heroin addict, and his mother struggled to raise their three young children on her own.

Tired of being poor, Sole joined a local gang at 14 and quickly moved up through the ranks selling drugs. He came of age in the early years of the War on Drugs, introduced by then President Richard Nixon.

Sole said, “We’d never heard of ‘mass incarceration’ back then, it was just our world. I could see that something wasn’t right, but I didn’t have the language for it yet. Police officers pulled me over where ever I went, constantly asking me for ID since I was a kid. I didn’t have any ID yet, and this happened to every Black guy I knew. I was upset at the world, upset at the police, upset that my gang friends were dying before they were old enough to go to high school.”

Black in a mostly-White school

When he turned 16, Sole’s mother shipped him off to relatives in Waterloo, Iowa – hoping to save his life. He was on the all too familiar trajectory of a Black man likely to die young.

Sole said, “You have to understand that a gang is not a play thing. It has structure; there were leaders and soldiers 500 deep in my South Side neighborhood. If I was going to survive, I had to make a plan because there were no outlets.”

Sole went from the nearly all-Black public school system on the South Side of Chicago to the nearly all-White Waterloo school district. He became captain of the basketball team in his new high school, and set a track and field record while maintaining good grades. He’s a tall guy, a really tall guy, and a naturally gifted athlete. Sole said, “I was smart and good at sports, but I was stigmatized for being a gang banger from Chicago. That label limited my opportunities.”

When he graduated from high school, Sole went home to his family in Chicago. He had enlisted in the Air Force, passed all of their admissions exams, but ultimately was rejected for having had childhood asthma. According to Sole, “Most of the kids in my neighborhood had childhood asthma; I hadn’t used an inhaler since eighth grade.”

Sometimes Sole wonders how things could have played out differently. He said, “I tried to join the Air Force, but I became a soldier on the streets instead.”

Vacation turns to probation

He worked a few low-paying jobs in Chicago, before deciding to get a fresh start in St. Paul. He had a friend he could stay with here, but conceded, “My friend wasn’t exactly living his best life.”

Soon Sole wasn’t either. At 19, he was caught with an unregistered firearm. The legal age for carrying a weapon in Minnesota is 21. He said, “I came to St. Paul on vacation, and got stuck here on probation.” Jason Sole’s long journey through the criminal justice system had begun.

At 21, he was convicted of second-degree possession of a controlled substance. By the time Sole was granted early release, he knew the only way he would ever succeed was to get an education.

Redemption through education

In December 2006, Sole received his bachelor’s degree in criminal justice while serving time for his third felony offense. The prison allowed him two hours to attend his commencement ceremony. When he walked across the stage at the Minneapolis Convention Center, Sole said, “The place exploded in cheers. I got my redemption in that moment.”

He continued to study the criminal justice system in graduate school.

Sole said, “I endured years of imprisonment, and a lot of trauma (including being shot) before I figured out how I wanted to live my life. I’m grateful for the perspective I have, grateful for the grace, grateful for my wife and daughters, grateful to be alive. Most people in my old neighborhood ended up dead or in jail for a very long time. I was one of the lucky ones.”

Better solution than police and prison

Dr. Jason Sole is now an adjunct professor in criminal justice at Hamline University, and a national keynote speaker and trainer. He has served as president of the Minneapolis NAACP, been a faculty member at Metropolitan State University, and is creating liberation programs for people of color across this community. He believes there is a much better solution to crime prevention than the present-day system of policing.

In 2013, he received a Bush Fellowship and focused on reducing recidivism rates among juveniles in Minnesota. In 2016, he published, “From Prison to Ph.D: A Memoir of Hope, Resilience, and Second Chances.”

In 2018, he was recruited by Saint Paul Mayor Melvin Carter to be director of the newly created Community-First Public Safety Initiatives. After the mayor spent $900,000 hiring additional police officers in 2019, Sole resigned on Martin Luther King Day.

He does not regret his decision, saying, “Look what happened! There was more gun violence in Saint Paul last year than ever before. Adding to the police force didn’t make anybody safer; it actually made us less safe. We can hold people accountable without putting them in cages.”

Sole continued, “Abolishing the police doesn’t mean there won’t be accountability for people who harm others. Divesting from police means that money can be used to house the unhoused. Divesting from police means that we can provide culturally specific drug treatment for those struggling with addiction. Divesting from police means that we can provide more jobs and better training to youth. We need to invest in people on the bottom rungs of society. That’s where real change will come.”

Humanize My Hoodie

There are many ways that Sole stands up to the system, and challenges the status quo. Not long after 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was fatally shot while wearing a hoodie, Sole started teaching his college classes wearing one. The goal was to help his criminal justice students get more comfortable with a black man dressed that way.

Sole’s ongoing “Humanize My Hoodie” Project is designed to end the senseless police killings of Black and Indigenous People of Color; to reinforce the truth that Black men in hoodies are valuable human beings not meant for target practice. Along with his high school friend, fashion designer Andre Wright, Sole turned the “Humanize My Hoodie” project into a movement with their custom designed sweatshirts, art installations, and workshops.

For more information on Jason Sole’s work and the “Humanize My Hoodie” movement, visit: www.humanizemyhoodie.com

Writer’s note: This piece neither reflects nor contradicts the editorial position of this newspaper. It is offered as a conversation starter on the subject of policing, and a reminder that each of us is the product of our experiences. What experiences have shaped your attitude toward the police in this city? What kind of changes do you hope to see and why? Direct your comments to the editor at tesha@LongfellowNokomisMessenger.com.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here